How we got here…

In 1761 Francis Egerton, the 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, built England’s first modern canal, revolutionising transport, and triggering an investment boom that transformed the nation. Two and a half centuries later his innovation reverberates in the form of 2000 miles of canals and towpaths throughout the UK, 100 miles of which are home to thousands of boats that constitute one of the city’s fastest growing and most vibrant communities.

Eastern European construction workers, young creatives, IT specialists, pensioners on fixed incomes… all find refuge from 21st Century real estate prices on London’s waterways. Amsterdam’s canals are older. Venice’s may offer better honeymoon photos. Neither boasts a community with the human energy of London’s aqueous avenues. From Harlesden and Southall in the West, to Camden and Hackney in the East, it’s a navy of newcomers, sharing tips and supporting each other with the help of a London Boaters Facebook group with more than 13,000 members.

How I got here

As an American, and frequent visitor to an elderly Aunt in London, I would run on the towpath and be transfixed. Who lived in these improbably elongate, mysterious vessels? Lined up bow-to-stern, two boats deep in mile-long rows. More often moored than moving? What life stirred inside them? Sealed tight, they held their secrets as securely as limpets cemented to a rock.

When Aunt Rose passed on, we tested her home’s rental value on Airbnb. My first lodger was a young German on his way to Manchester to retrieve a boat to bring to London. He shared the secret of how to live in one of the world’s most expensive cities on a continuous cruising license for 800£/year. A few months later, when it became clear that Airbnb rentals couldn’t pay the inheritance tax, we turned the keys over to a realtor and I moved into the motorman’s room in the stern of Max’s boat, 70 square feet as economically arranged as a Mercury rocket space capsule. For two months I called it home.

When Rose’s house sold, I used my share to buy a boat, the prettiest one I could find, a wide beam, stable enough to support theatrical productions on its roof, by actors I would hire to lead interactive tours. I envisioned a legacy project in the memory of my Aunt Rose, winner of a British Film Institute Lifetime Achievement Award for her work in casting. In the course of day-long tours, actors would tell the story of the canals, their role in the industrial revolution and the growth of modern London. “The world’s greatest story tellers telling one of the world’s great stories.”

But after 18 months, “Bards on Boats” failed to launch. Not because there weren’t enough actors steeped in canal lore, eager to share their knowledge and ready to work. There was simply nowhere to base the operation. Without a fixed mooring — rare as hen’s teeth in central London — I was prohibited from selling tours. Required by the Home Office to create two jobs as a condition of my entrepreneurial visa, I had to come up with something new.

Or something old.

In my prior life, running community development projects on the U.S.-Mexico Border, I had a modicum of success securing grants. Later, working for the Yale Climate and Energy Institute, I’d become conscious of my carbon footprint, something life on a canal boat lowers considerably, but not nearly as low as it will be when London inevitably follows Amsterdam’s lead and eliminates diesel engines from the waterways. The crazy popularity of canal boats has already made it hard to get a qualified carpenter, electrician or plumber to work on your boat. What will happen when mechanics are needed to swap out 5,000 engines?

Bullets to Barges

Prior to Covid-19, knife crime was London’s most talked about problem with millions of pounds set aside for related programs. Could canal boat living, and associated vocational opportunities, be tools to address the problem? Every tradesperson I’d met in the course of renovating Molly Anna — the electrician who plays in a cover band, the diesel mechanic with his contortionist wife, the welder with cameo appearances on Youtube and Netflix — were eccentric, charismatic personalities who connect with kids. Specifically, kids who don’t fit in. They may have been outsiders themselves. Whether or not it was because going to sea is a traditional passage to manhood in this maritime nation, or they just wanted to share their own story of making a successful life for themselves on the water, every one of them signed on. In November, I began assembling the paperwork to create Your Canal Boat CIC, whose programs would include using the canal boat experience to interest youth in trades programs, and give them the skills to refurbish old canal boats, in anticipation of a day when every boat needs an electric engine.

And then… Covid-19

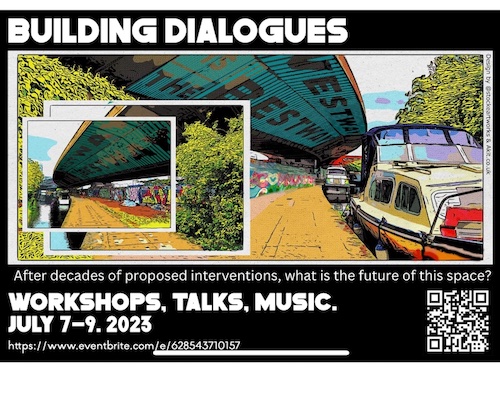

Shortly after we’d signed up the requisite number of Directors, however, and formally constituted the new company, Covid-19 came along. The world went dark. By summer, when “non-essential” shops opened, and cafes and restaurants began operating under new rules, London’s world-leading entertainment industry remained shuttered. Actors and musicians were stymied as had been Bards on Boats: they had no place to base their work. Come Fall, strict limits on indoor seating still favour outdoor events. And with outdoor venues in short supply, London’s 200-year old canal network suddenly has fresh 21stCentury relevancy, as home to boat-based canal-side performance. Hence, Your Canal Boat CIC has a second imperative mission: identifying and developing suitable locations for musicians and actors to perform on boats licensed and insured for the purpose. The first of them is scheduled for September 20, at Mary Seacole Memorial Park in Harlesden.