I didn’t recognise the guy strumming guitar atop my boat. My music critic brother back in America, however, did.

“You punk rock ignoramus,” he lovingly texted. “Tell him ‘Up the Bracket’ is my #1 Spotify track of the year.”

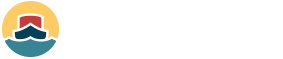

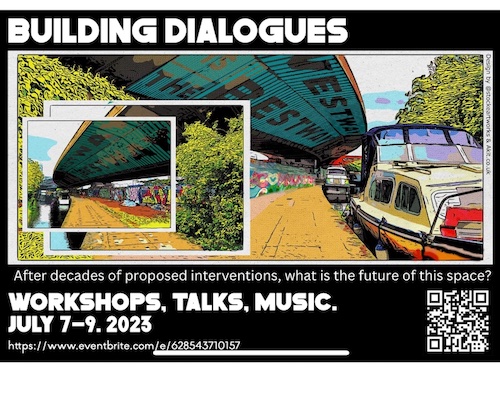

Almost Christmas, at the tail end of a 3-year visa and a questionably timed effort to demonstrate that Londons’ canals were a natural home for live performance, I was moored at Kings Cross. My savings were spent. My house in Texas was sold. I had nothing left but the Molly Anna, a wide beam canal boat equipped with a full length stage and a license from the Canal and River Trust to amplify music for passersby.

Unable to pay performers, I turned to open mics to keep going. If musicians would play for free, I figured, audiences would brave the elements. And if the setting wasn’t conducive to ticket sales, the circumstances of Covid and the need to keep music alive and people safely gathering could unlock grants to fund my proposition: that the city’s watery matrix hid dozens of Covid-secure places for performance.

If you moor there, will they come? Between London’s status as a global nexus for aspiring artists, its shortage of live venues and the sturdy constitution of a populace tempered by the weather — I bet they would.

Is your name Peter, I asked? Just to make sure. “Because you’re causing a bit of a commotion inside my boat.”

He confirmed it was him, and asked if he could play. He’d return Sunday morning he said. Fat chance said my crew back in the boat. “Not if he’s got a concert.” He’d be up late partying they assumed. Nice try though.

Come morning my team wasn’t there, but Pete Doherty was. Along with a retinue including his keyboard playing wife, Katja, from the Puta Madres, and his sled dog — which settled down to study the swans from the roof of a narrowboat double-moored next to me.

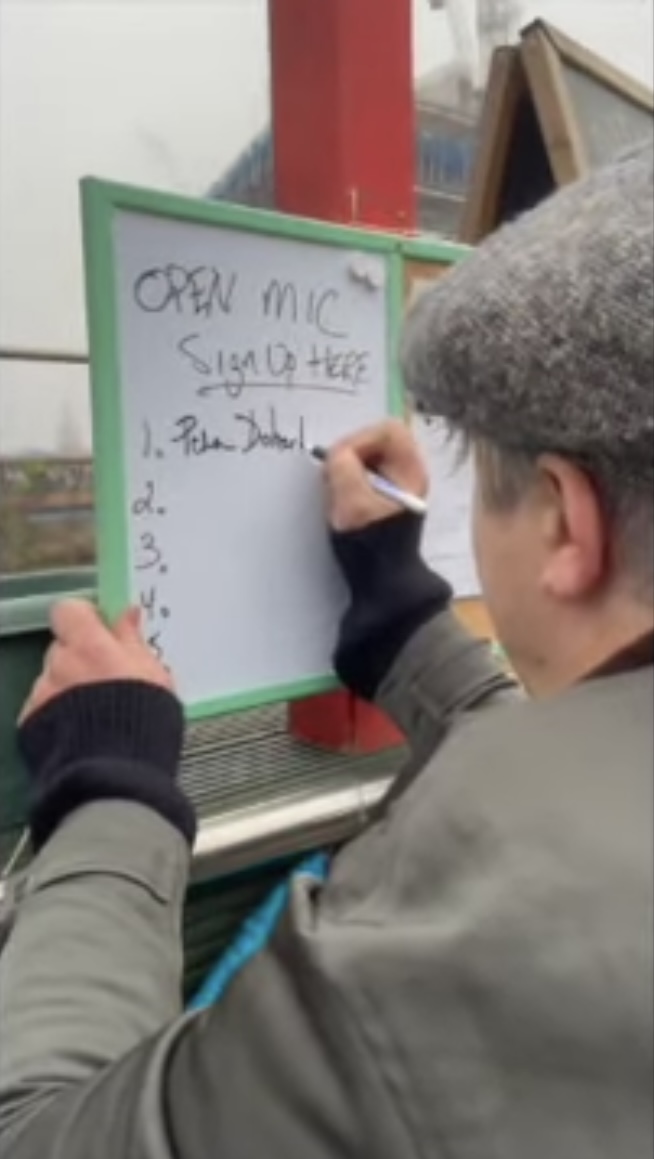

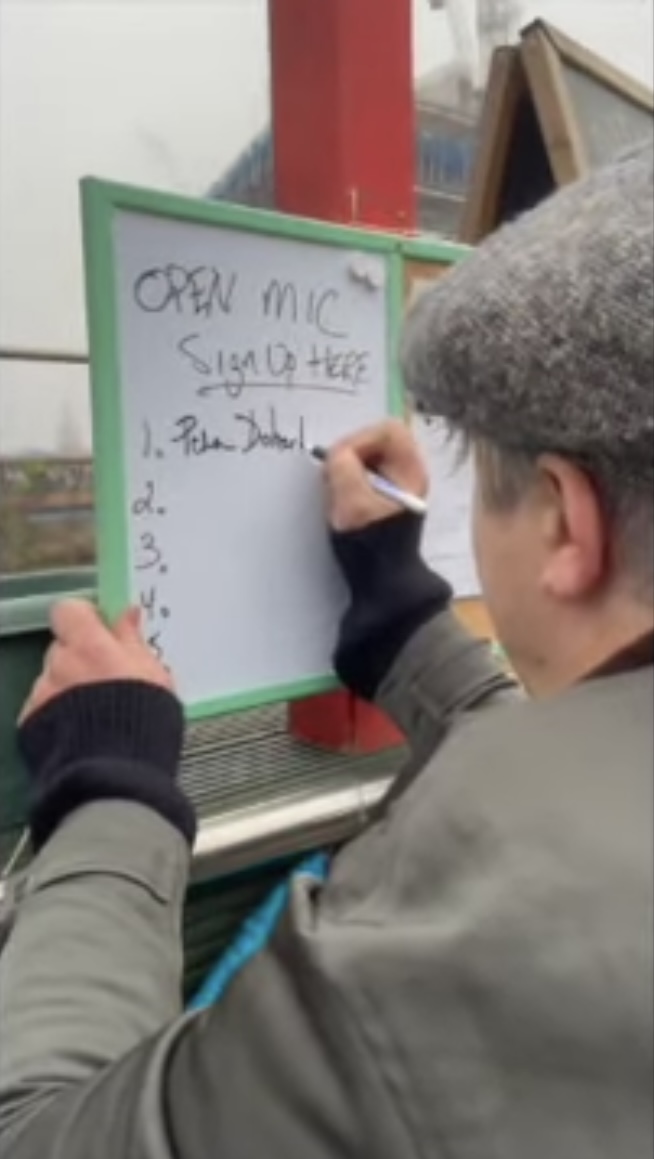

A mate tuned Pete’s guitar while I fumbled with the sound system. He was about to start when I remembered he’d neither signed in, nor recorded the statement I wanted every artist to make. Who were they? And why were they playing for free in the cold? Useful for future grant applications, I hoped. Would he mind?

“My name is Pete Doherty,” he spoke into the mic. “I’m an artist and a dreamer…. and it may sound corny as hell, but to be here on someone’s canal boat playing music… it’s just that kind of Arcadian vision that in the midst of everything…. the pandemic and all the evils in the world, we can still have these moments of joy.”

And then he created one. Roaming my stage with an acoustic guitar, a teddy bear of a man, playing for sheer pleasure. Upbeat tunes with a lilting refrain:

“In Arcady life trips along. It’s pure and simple as the shepherd’s song.”

Confirmation was swift. A cyclist with a guitar on his back turned out to be a doctor from Galway in love with Woody Guthrie more than his job with the NHS. He climbed down and a crooner who’d just arrived from Bahrain climbed up. Followed by a Japanese keyboardist who sang like Elton John, but whose English revealed he’d just arrived too. Your standard ridiculously varied London open mic.

Serving mulled wine through a porthole, my friend Martyn, a professional roadie on break from tour, thought he recognised Pete Doherty in the audience.

“Pete who?,” I demonstrated my ignorance of ‘90s-era punk idols.

Everyone craned to look. Was the grown man with Siberian husky and satchel full of books just purchased from the Book Barge the same baby-faced fashion plate they remembered from newspaper headlines fifteen years ago?

Could be they agreed. His band was in town for a concert. Go speak with him, they told me. Fearless with celebrities unknown to me, I approached.

Christmas shoppers stopped to shoot video. My angry boater neighbour, who’d quarrelled with me the day prior, now flashed a huge thumbs up. I introduced the next performer, a slightly star-struck 21 year old rapper. When I couldn’t get Gabriel’s backing tracks to play, Pete plopped into a chair and improvised acoustic beats.

They jammed for half an hour and then it was over. Before his manager hustled him off, Peter arranged free recording time in his London studio for Gabriel. Katja invited me and my absent crew to see the band that night.

In the interim I Googled “Pete Doherty” to fill in the gaps of my musical education. There was a lot there. Between scrapes with the law, episodes of rehab and celebrity girlfriends, he’d made easy work for the tabloids. Hijinks they could sensationalise, but which obscured the man’s message of buccolic life in a pre-industrial landscape he calls Arcady.

Thirty years since he first put that utopian vision into lyrical form, older and wiser, the drugs behind him, it remains his muse, evidenced by his song choice that morning, inspired by the opportunity to play in a canal side setting that preserves simpler times.

Looking down on an audience of thousands from our reserved seats above the Kentish Town Arena’s stage that night, I thought “what a great show”. It was easily the second best I’d seen that day

Confirmation was swift. A cyclist with a guitar on his back turned out to be a doctor from Galway in love with Woody Guthrie more than his job with the NHS. He climbed down and a crooner who’d just arrived from Bahrain climbed up. Followed by a Japanese keyboardist who sang like Elton John, but whose English revealed he’d just arrived too. Your standard ridiculously varied London open mic.

Serving mulled wine through a porthole, my friend Martyn, a professional roadie on break from tour, thought he recognised Pete Doherty in the audience.

“Pete who?,” I demonstrated my ignorance of ‘90s-era punk idols.

Everyone craned to look. Was the grown man with Siberian husky and satchel full of books just purchased from the Book Barge the same baby-faced fashion plate they remembered from newspaper headlines fifteen years ago?

Could be they agreed. His band was in town for a concert. Go speak with him, they told me. Fearless with celebrities unknown to me, I approached.